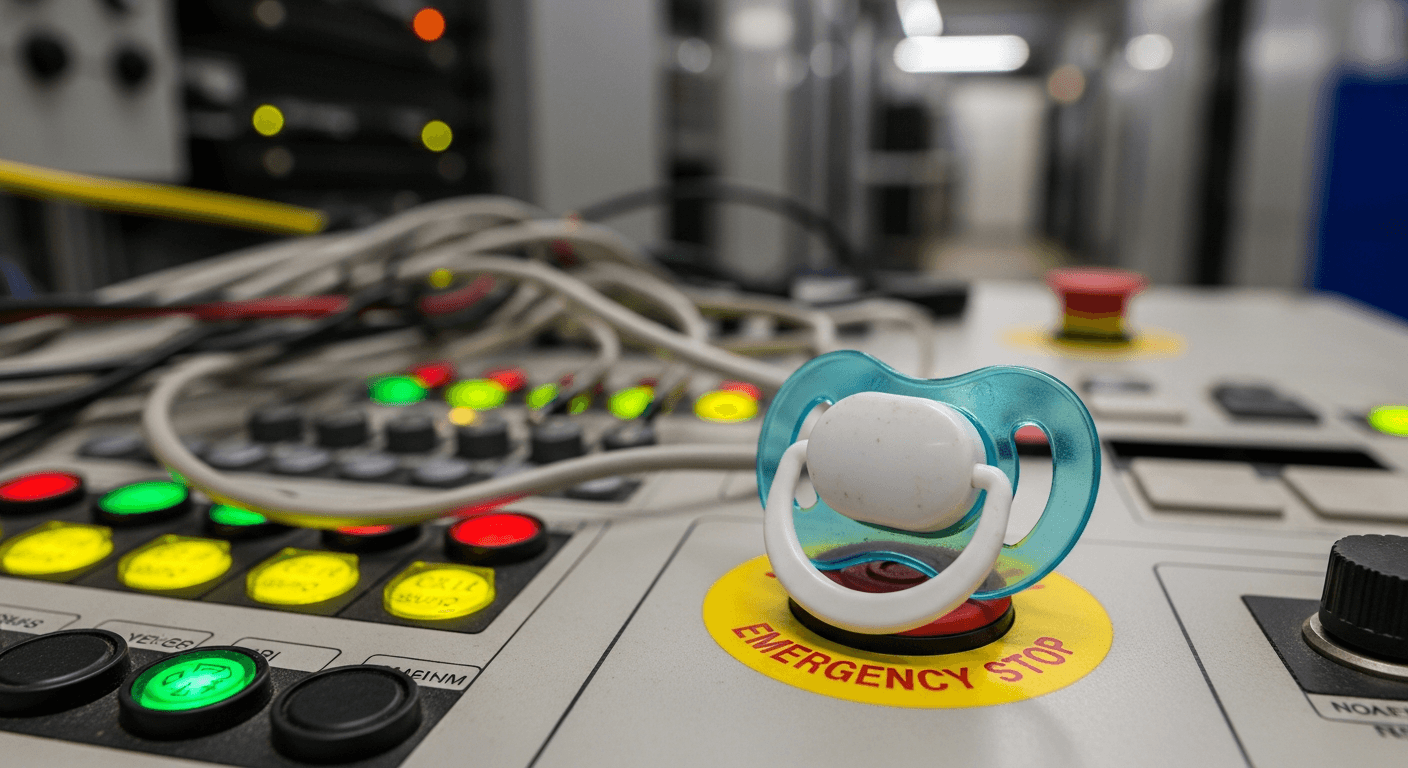

If Your ‘Automation’ Needs Babysitting, It’s Not Automation

Tuesday, 13 Jan 2026

|

The uncomfortable truth: if your “automation” needs babysitting, it’s not automation.

If you’re constantly watching dashboards, re-running jobs, fixing “exceptions,” or checking whether the bot did what it was supposed to do, it looks like work, not failure. That’s why competent teams normalize it. You’re protecting service, keeping freight moving, and avoiding the fire drill that happens when a tender is missed or an invoice is wrong.

But babysat automation is expensive. It hides inside good intentions, it burns your best operators’ attention, and it quietly raises cost-to-serve while everyone is “busy.”

What babysat automation looks like in freight ops

It’s rarely one big broken tool. It’s lots of small manual tasks wrapped around an “automated” step.

Here’s the pattern: an automated action exists, but a human still has to do the work that makes the action safe.

Common examples across brokerage and shipper operations:

- TMS “auto-tender” that still needs someone to verify acceptances, chase non-responses, and re-tender.

- EDI/API feeds that “work” but require daily checking, reprocessing, and spreadsheet reconciliation.

- Appointment scheduling portals that still require copy/paste, email follow-ups, and exception handling.

- Rate uploads that run nightly but need a morning cleanup for invalid lanes, missing accessorials, or rounding issues.

- Auto-audit that flags “exceptions” so broadly it becomes a second invoice review team.

The tell is not that exceptions exist. Freight always has exceptions. The tell is that the automation created a new layer of routine supervision.

Work-about-work: the hidden operating system

Babysat automation creates work about work. It doesn’t move freight; it manages the automation.

Micro-tasks you’ll recognize:

- Checking if jobs ran

- Re-running failed jobs

- Manually nudging stuck workflows

- Hunting down why a record didn’t match

- Maintaining “do not use” lists

- Updating mapping tables

- Creating manual “bridge” files

- Sending “just confirming” emails because you don’t trust the system

- Screen-scraping or copy/paste because integrations are brittle

And the meta-work:

- Building special instructions to compensate for tool behavior

- Training new hires on tribal steps that aren’t in SOPs

- Creating “backup” spreadsheets that become the real system

- Holding daily standups just to coordinate what should be deterministic

If you have to coordinate humans to make the automation reliable, the automation isn’t reliable.

Why competent teams normalize babysitting

This is where it gets tricky: the teams doing the babysitting are often your strongest.

Heroics feel like service

Operators step in because they can’t let service slip. They’d rather patch today than redesign tomorrow. In freight, that’s rational.

Tribal memory becomes a safety net

People learn the quirks:

- “It fails if the ZIP has a leading zero.”

- “Don’t run that report before 7:10 AM.”

- “If the carrier name has ‘Inc.’ it won’t match.”

Those are not process controls. They are folklore. And folklore doesn’t scale.

Urgency crowds out root cause

When volume spikes, you accept the babysitting as “just how we do it.” Then it becomes permanent.

The cost is smeared across roles

No one line item says “automation babysitting.” It’s minutes spread across coordinators, analysts, team leads, and managers. That makes it invisible.

The 4-symptom checklist

If you’re not sure whether you have babysat automation, use this quick checklist. If you have 2 or more, you have a real opportunity.

1) You have a daily “system check” ritual

Someone must confirm integrations ran, tenders went out, invoices posted, or statuses updated.

2) Exceptions are the norm, not the edge

A meaningful portion of transactions requires manual review because the rules are too broad or too fragile.

3) Your best people are “glue”

Top operators spend time reconciling, interpreting, re-keying, and validating instead of improving flow.

4) You keep parallel trackers

Spreadsheets, shared inboxes, and chat threads exist because you don’t trust system state.

Root causes (and the fixes that actually stick)

Babysitting isn’t a moral failure. It’s usually one of these design gaps.

Undefined “done” states

If the system can’t tell whether a load is truly covered, a tender is truly accepted, or an invoice is truly payable, humans will.

Fix:

- Define a small set of states that reflect operational truth (not just system fields).

- Make state transitions explicit and testable.

- Add “blocked because…” reasons that are structured, not free-text.

Exceptions without routing

If exceptions land in a generic queue, they become everyone’s problem.

Fix:

- Categorize exceptions into 5–10 buckets you can staff and improve.

- Route by ownership (carrier sales, track-and-trace, billing) with a time SLA.

- Require an exception to have a next action, not just a flag.

Automation without guardrails

If rules are too aggressive, operators must constantly undo or override.

Fix:

- Add conservative thresholds and “safe fail” behavior.

- Use “suggest then commit” where risk is high (e.g., accessorial approval).

- Log why a decision was made so humans can trust it.

Data contracts that drift

Partner data changes. Internal naming changes. New accessorials appear. The integration is “working,” but semantics broke.

Fix:

- Maintain a small set of data contracts (required fields, allowed values, tolerances).

- Add monitoring for drift (not just downtime).

- Quarantine bad records automatically with a clear reason.

Quiet math: what babysitting really costs

No benchmarks here, just conservative illustrative math you can adjust.

Assumptions (tune to your operation):

- 6 operators touch “automated” workflows daily

- Each spends 35 minutes/day on babysitting tasks (checks, reruns, reconciles, follow-ups)

- 22 working days/month

- Fully loaded cost: $35/hour (wage + burden; use your own number)

Math:

- Daily babysitting time = 6 x 35 min = 210 minutes = 3.5 hours/day

- Monthly time = 3.5 x 22 = 77 hours/month

- Monthly labor cost = 77 x $35 = $2,695/month

- Annualized = $32,340/year

Now add the non-labor cost that usually matters more:

- A delayed tender that causes a same-day recovery scramble

- A missed appointment window that creates detention

- An invoice error that adds a week to cash cycle

You don’t need a dramatic failure for this to hurt. The steady tax on attention reduces throughput. If those 77 hours/month were redirected to proactive carrier coverage, appointment lead time reduction, or dispute prevention, you’d see margin and service lift without adding headcount.

The reliability test: would you leave the room?

A practical definition of automation in operations: you can leave the room and it still works.

Ask this about each “automated” step:

- If no one checks it until end-of-day, what breaks?

- If it breaks, do we know within 15 minutes?

- When it breaks, does it fail safe or fail loud?

- Can a new hire follow the recovery steps without tribal knowledge?

If the honest answer is “we’d rather not try,” you’ve found babysitting.

A 30-minute exercise to locate and kill babysitting

Do this with one team lead and two operators who do the real work. Set a timer. The goal is not a perfect map; it’s to surface the hidden loops.

Step 1 (10 minutes): List the babysitting touches

Pick one workflow (examples: tendering, appointment scheduling, invoicing, track-and-trace).

Write every manual touch that happens after the “automated” step runs.

Use bullets. Keep it raw.

Step 2 (10 minutes): Label each touch as one of three types

For each bullet, mark:

- Verification (checking that the system did it)

- Recovery (fixing failures)

- Compensation (doing extra work because the automation is incomplete)

Then circle the top 3 that happen most often.

Step 3 (10 minutes): Convert one touch into a system behavior

Pick the most frequent circled item and define:

- Trigger: what event should start the check/recovery automatically?

- Signal: what data proves success or failure?

- Route: who owns it if it fails?

- Timer: how long before escalation?

You’re not building software in this exercise. You’re turning tribal supervision into explicit rules and ownership. That’s the bridge from babysitting to automation.

“But we already have automation…”

You probably do. The issue is that you have automation that stops at the action, not automation that owns the outcome.

Common objections, handled plainly:

“Exceptions are unavoidable in freight.”

Correct. The goal isn’t zero exceptions. The goal is:

- fewer predictable exceptions

- faster routing of real exceptions

- less time spent on verification

“Our volume is too variable to standardize.”

Variability is exactly why you need clear states, routing, and safe failure modes. Standardization doesn’t mean rigidity; it means predictable recovery.

“We can’t integrate with every carrier or customer.”

You don’t need to. Start by making your internal workflow deterministic:

- normalize inputs

- quarantine bad data

- create a single exception queue with categories

Then integrate where it pays. Babysitting often drops before new integrations do.

“The team knows how to handle it.”

They do, and that’s the risk. If your process depends on your strongest people remembering the tricks, you’ve built a fragile system. Turn their knowledge into guardrails so they can work on higher-leverage problems.

What real automation buys you: margin, speed, and calm

When automation stops needing babysitting, three things happen quickly:

- Throughput rises because operators stop doing verification loops.

- Cost-to-serve drops because “invisible minutes” disappear.

- Service stabilizes because exceptions are routed, timed, and owned.

You don’t need a giant transformation. Pick one workflow, expose the babysitting, and replace one manual supervision loop with explicit rules and monitoring. Repeat.

If you want help identifying where your automation is quietly taxing your operation, book a demo and we’ll walk one workflow end-to-end and quantify the babysitting load.